Embarking on a journey through the corridors of scientific history unveils a trove of fascinating but utterly bizarre theories that were once embraced as unassailable truths. In the pursuit of understanding the world around us, some of the brightest minds in various eras have put forth ideas that, by today’s standards, appear nothing short of insane. From unconventional explanations of natural phenomena to intricate speculations about the cosmos, this blog delves into the annals of scientific thought to unearth 10 mind-boggling theories that were once considered factual. As we explore these historical beliefs, we gain not only a glimpse into the evolution of scientific understanding but also a healthy dose of appreciation for the scientific method that continually refines our comprehension of the universe.

The List of 10 Insane Scientific Theories Believed To Be Fact

1. Spontaneous Generation

The concept of spontaneous generation, originating in the Roman era, posited that living organisms could arise from nonliving matter. Examples included the belief that mice could emerge from concealed food and maggots spontaneously generated from decomposing meat. Observations such as maggots appearing on spoiled meat and mice mysteriously emerging in covered bread and cheese stored in dark areas fueled this theory. In the 17th century, there were even claims that mice could be created by enclosing wheat husks in a damp cloth and leaving them in an uncovered jar for 21 days. Despite several scientists challenging spontaneous generation over the centuries, no definitive experiments refuted it, and supporters occasionally manipulated results to reinforce their stance. However, in 1859, Louis Pasteur conclusively debunked the theory, marking a pivotal moment in the history of scientific understanding.

2. Miasma Theory

In the Middle Ages, medical practitioners adhered to the notion of miasma, a perilous airborne vapor believed to be the source of various diseases. The term “malaria,” meaning “bad air” in Italian, exemplifies the association of diseases with corrupted air. During the Great Plague of London, doctors took measures like placing flowers in face masks to shield themselves from the presumed malevolent air, although it proved ineffective against the plague. Paradoxically, the fear of miasma did prompt initiatives toward cleaner environments, spurred by the misconception that decaying substances and creatures released these harmful vapors. Renowned figures like Florence Nightingale emphasized cleanliness in hospitals to combat the perceived threat. However, the lack of accurate knowledge led to unintended consequences, such as the unwitting transmission of diseases by doctors who neglected to wash their hands. The decline of the miasma theory in the 1800s coincided with the emergence of the germ theory, revealing the role of microorganisms like bacteria in causing illnesses—a foundational concept that persists in modern medicine.

3. Maternal Impression

Until the early 20th century, there existed a widespread belief in maternal impression, asserting that a pregnant woman’s experiences could influence the development of her fetus. It was contended that what a mother heard or saw during pregnancy could shape specific attributes of the child. For example, it was believed that exposure to loud noises could lead to the birth of a deaf child, while witnessing certain sights might result in visual impairments. To mitigate these perceived risks, doctors advised pregnant women to engage in pleasant activities, such as visiting art galleries and music concerts. The case of Mary Toft in 1726 highlighted the exploitation of this belief, as she deceived doctors into thinking she had given birth to rabbits, capitalizing on claims related to her interactions with rabbits. Notably, figures like Joseph Merrick, known as the Elephant Man, were erroneously linked to maternal impression, with the belief that his deformities resulted from his mother’s scare involving an elephant during pregnancy. Today, we understand Merrick’s conditions to be associated with neurofibromatosis and/or Proteus syndrome.

4. Telegony

Telegony, a belief attributed to the ancient Greek philosopher Aristotle, posited that traits from a woman’s former sexual partner could be inherited by a child conceived with another man. Although widely accepted in the past, particularly evident in Greek mythology where heroes often had both human and divine fathers, telegony has been debunked in contemporary understanding. This historical notion influenced various societal norms, such as restrictions on British kings marrying previously married women, exemplified by the 14th-century controversy surrounding the intended marriage of Edward the Black Prince and Joan of Kent. The discrediting of telegony occurred in the 19th century with the establishment of genetics as the determinant of offspring traits. Intriguingly, in 2014, researchers at the University of New South Wales discovered telegony effects in fruit flies, where the size of offspring was influenced by the first male fly the female mated with, persisting even after subsequent matings.

5. Caloric Fluid Theory

In contemporary understanding, we recognize heat as a distinct form of energy that follows the principles of conservation, unable to be created or annihilated but rather transferred between various forms. However, centuries ago, this comprehension eluded people, and in 1787, French chemist Antoine Lavoisier introduced the caloric fluid theory, asserting that heat was a fluid substance that could move from a hotter body to a cooler one. Lavoisier proposed that as the cooler body received more caloric fluid, it would heat up. This theory served as the prevailing explanation for numerous heat-related phenomena at the time, including the temperature increase observed during compression, attributed to the squeezing of caloric fluids into a smaller space. Eventually, the caloric fluid theory was debunked, marking a pivotal shift in our understanding of heat.

6. Humoral Theory

In adherence to the humoral theory, individuals were believed to possess four humors—blood, phlegm, black bile, and yellow bile—each associated with one of the four elements (air, earth, water, and fire) and linked to a specific season. The theory postulated that imbalances in these humors, exacerbated during certain seasons, could lead to health issues, necessitating medical intervention. Remedies varied, ranging from prescribed exercises, dietary adjustments, and medications to more extreme measures such as creating blisters with a hot iron or administering laxatives. In severe cases, physicians resorted to draining the excess humor from the body. However, the humoral theory, prevalent in the past, was discredited in the 1800s.

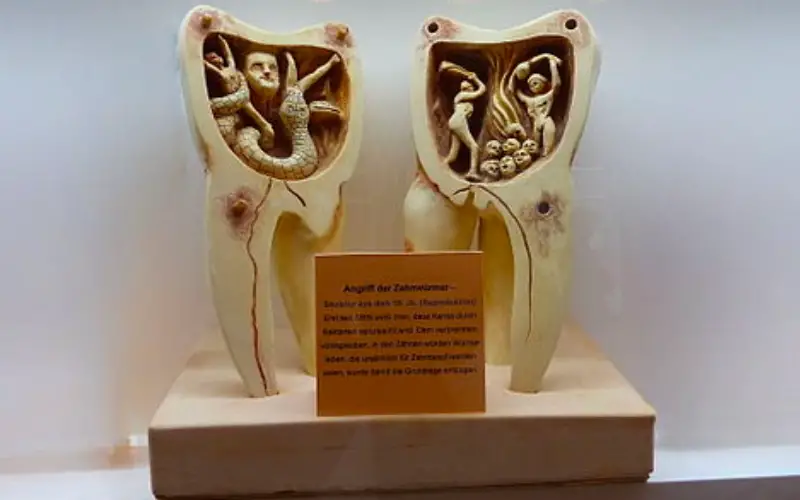

7. Tooth Worm

Centuries ago, the prevailing belief among scientists attributed toothaches to the presence of a worm within the tooth, commonly known as the tooth worm. This theory, dating back to around 5000 BC, persisted until the 18th century when it was debunked upon the realization that bacteria, not worms, were responsible for tooth decay. Prior to this revelation, proponents of the tooth worm theory argued that the worm, purportedly residing at the tooth’s root, triggered toothaches when in motion, with pain subsiding when the worm rested. The theory gained some support from the resemblance of the nerve at the tooth’s base to a worm. However, disagreement persisted among scientists regarding the appearance of the hypothetical tooth worm, with British scientists likening it to an eel and German scientists suggesting a maggot. Even after its debunking in the 18th century, some held onto the notion that tooth worms caused toothaches, a belief that endured until the 1900s.

8. Geocentric Model Of The Universe

The geocentric model, one of astronomy’s ancient theories, posited that the Earth occupied the central position in the universe, with all celestial bodies, including the Sun and planets, orbiting around it. While accurate for the Moon, it did not hold true for other celestial entities. This concept originated with Anaximander in the sixth century BC, asserting that the Earth resembled a cylinder. Although subsequent philosophers like Plato, Pythagoras, and Aristotle acknowledged the Earth as a sphere, they retained the notion of its centrality in the universe. Despite challenges to the geocentric model in the tenth to 12th centuries, it endured until the 16th century. Nicolaus Copernicus revolutionized astronomical thought with his proposition that the Earth was not the universe’s center, as detailed in his seminal work, “De revolutionibus orbium coelestium” (On the Revolutions of the Heavenly Spheres). Copernicus, aware of the controversy, released his findings on the brink of death. Ultimately, the geocentric model yielded to Copernicus’s heliocentric theory in the 17th century.

9. Preformationism

In the 17th and 18th centuries, a prevailing medical belief known as preformationism held that human sperm or eggs housed minuscule preformed humans that developed in the womb. This concept extended to animals and insects, with scientists asserting the discovery of tiny winged creatures within chicken embryos. The advent of more advanced microscopes, however, debunked preformationism. Through careful observation of human and animal eggs, sperm, and embryos, scientists found no evidence of miniature beings within them. Consequently, preformationism gave way to the more accurate understanding of embryonic development known as epigenesis.

10. Hollow Earth

The Hollow Earth theory, distinct from previous theories, never gained widespread acceptance within the scientific community, and its validity remains unsupported by evidence, contradicted by established knowledge about the Earth. Originating in 1692 from Edmund Halley, the namesake of Halley’s Comet, this theory emerged when he noted fluctuations in the Earth’s magnetic field. Halley proposed a hollow Earth comprising four spheres, with the outermost being the Earth as we perceive it. The spheres progressively shrink towards the innermost part. While some scientists endorsed Halley’s idea, including suggestions of inner suns by Euler and Leslie, the theory has since been debunked, although divergent opinions persist.

Conclusion

As we conclude our exploration into the annals of scientific history, it becomes clear that the realm of human understanding is marked by a dynamic and ever-evolving process. The 10 insane scientific theories that were once fervently believed stand as poignant reminders of the ceaseless quest for knowledge and the occasional detours that mark the scientific journey. While these historical misconceptions may elicit a chuckle today, they underscore the importance of rigorous inquiry, empirical evidence, and the scientific method in separating fact from fiction. The legacy of these theories serves as a testament to the resilience of human curiosity and the collective effort to uncover the genuine truths that shape our understanding of the natural world.